How to Protect Witnesses Who Are Seen by Public and Police as Traitors?

The new trial of Saša Cvjetan before the Belgrade District Court is the first for war crimes in Kosovo in which ethnic Albanians have testified in a Serbian court. But, as in the case of a military trial of a Yugoslav Army captain and two privates for the murder of two Kosovo Albanians, the victims remained mostly unidentified. Prosecutors here obviously do not see themselves as representing the victims and do not go to the trouble of establishing their names. This, sadly, indicates that the names of Albanian victims do not matter to us in Serbia.

At the trial of Cvjetan, who is charged with the murder of 19 Albanian civilians in the Kosovo town of Podujevo during the NATO bombing in 1999, four children who survived looked straight at the panel presided by Judge Biljana Sinanović as they gave the names of their dead mothers, brothers, sisters, and by doing so went a long way toward restoring the human dignity of the victims. Correctly pronouncing all the names, Judge Sinanović repeated them for entry into the trial record. It seemed as if she was seeing all those women and children through the eyes of the four before her.

Albanian witnesses

It took a long while to persuade Kosovo Albanians to come to testify in Serbia, which for them is the epitome of all their pain and suffering. The four children remember well the uniforms of the Serbian policemen who shot their mothers and siblings after lining them up against the wall of Halim Gashim’s small house. Their fathers escaped with their lives only because they fled a couple of hours before the police arrived. Over several months, I talked with the fathers about truth and justice, and gradually they came around to my view that the courts and public in Serbia should hear the truth about what happened to their loved ones.

Since Serbia has no witness protection legislation or experience in this field, the protective measures were designed by the Humanitarian Law Center in conjunction with the War Crimes Investigation Unit of the Serbian Ministry of Internal Affairs. It was agreed with the children’s fathers, child psychologist and Judge Sinanović that all security personnel would be in civilian clothes, that they would include two members of the multi-ethnic police force from Preševo and Bujanovac, and that no marked police cars would be used. Because of their experience with war crimes trials in Kosovo, it was also agreed that UNMIK translators would be the court interpreters. The judge further instructed a local child psychologist to interview the children to evaluate their ability to testify. The protection team, headed by a well-trained and outgoing police officer, was with the witnesses around the clock. The day after the children arrived in Belgrade, the team took them to the zoo and on sightseeing trips. On one of these occasions, one of the children was heard to remark: “These weren’t in Kosovo; that’s why they are so nice.”

The children and their fathers testified in July 2003 and another four Kosovo Albanian witnesses in December that year. The second group was escorted by UNMIK police to the Merdare border crossing where they were taken over by the same team that provided protection for the first. Again, the team demonstrated a high level of professionalism and sensitivity toward the traumatized victims.

Enver Duriqi, whose four children, wife and parents were killed by Serbian police during the NATO bombing, was in the second group. As soon as the war was over and the Serbian forces had withdrawn from Kosovo, he went to the scene of the crime where his loved ones had been hastily buried and, with his bare hands, dug up a few marbles that belonging to one of his sons. Those marbles are his most prized possession. In the courtroom, he took a small white bundle from his pocket, carefully unwrapped it, and showed the marbles to the judges.

Duriqi and another Albanian witness were in the courtroom when the presiding judge had Goran Stoparić called in to testify. Hanging on to every word, they listened to this member of the Scorpions recount in detail how his special police unit made its way through Kosovo, driving Albanians from their homes, killing women and children.

Witnesses testifying against police

The defendant’s counsel, his family and wartime comrades began suspecting Stoparić’s “patriotism” as soon as they learned I had met with him in a cafe in the town of Šid. The local police called him in for questioning, wanting to know what we had talked about. Then his comrades began coming, asking if it was true that he was going to “betray the Serb nation.” As the trial approached, they warned him to desist or “nothing will save you.” Just before Stoparić was due to appear in court, on 10 December 2003, his former commander Boca offered him a substantial reward if he behaved “like a patriot should” and said the punishment for traitors awaited him if he did not.

I did not dare tell anyone that a former member of the special police forces had decided to speak out about the killing of Albanian women and children. The day before Stoparić’s appearance in court, I spoke with the Serbian Public Prosecutor, gave him a statement by Stoparić and requested protection for him. When I told the Prosecutor about the threats made by Stoparić’s former commander and the latter’s connections with the police, he replied that Stoparić need not be afraid, that the police, prosecutor’s office and court would do their job in the professional and responsible way envisaged by the law.

The first measure ordered by the court was that Stoparić would join the Albanian witnesses who were already under protection. He was taken to a room near the courtroom where he found Enver Duriqi, Florim Gjata, Rexhep Kastrati and Naim Veseli. In Serbian, Duriqi said, “For the first time, I feel better.” Gjata put out his hand to shake Stoparić’s, and Kastrati and Veseli said: “We were afraid to come to Belgrade, but it was worth it.”

The news of Stoparić’s “betrayal” had in the meantime reached Šid. First, the wall around his brother’s house was defaced with vulgar slogans. Then on 17 January 2004, Igor Szabo called Stoparić’s brother on the telephone and, speaking for himself and Milovan Tomić, another former member of the Serbian special police forces who carries a Croatian passport, threatened to fire a Zolja rocket into his house. Szabo also advised him to buy a wreath, saying his brother was a traitor and “a dead man.”

When Judge Sinanović’s order to place Stoparić under police protection came into effect, he was taken over by the Serbian Ministry of Internal Affair’s Protection of Persons and Facilities squad. Lt. Col. Dragan Veškovac assigned one of his captains to look after Stoparić. The witness was provided with decent accommodation and food, but it took the captain two weeks to get him a cellular phone card. Stoparić is a smoker but it appears that buying cigarettes, toothpaste and other necessities for people under their protection is not in the squad’s job description. He was never allowed outdoors and all he could do all day was talk with his family and friends on the phone, watch television, read and sleep. In one and a half months, the captain charged with his safety came to see him ten times at the most. As a rule, he would hurry into the room, ask Stoparić if he was sticking to the rules, and then hurry out again.

For the New Year holidays, he arranged for Stoparić to be temporarily relocated so that he was able to spend some time with two friends from Šid. The next day, all Šid knew that Stoparić was housed in a singles apartments building in Belgrade’s Bežanija district. Stoparić feels that the captain too saw him as a traitor. In a nutshell, witness protection as provided by the squad consists of isolation and mental torture.

Judge threatened

Judge Biljana Sinanović has been receiving threats for months. In July 2003, just after the Albanian children and their fathers had left Belgrade, there was an explosion outside the Palace of Justice. Since then, she has on several occasions found threatening notes under her windshield wiper and the tires of her car have been let down twice.

Witness questioned by police

On 4 February, the day before he was due to testify in court, Nebojša Cekić was questioned by police about the subject matter of the trial. He told the court that the three inspectors behaved correctly. But this nonetheless constitutes pressure on witnesses and could lead them to reconsider telling the truth in court.

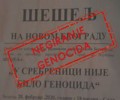

Future of war crimes trials The prevailing view in Serbia is that war crimes suspects should be tried by domestic courts rather than the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia. This is something the international community would also like to see and has provided Serbia with major funding to make it possible. The money was used to modernize and equip courtrooms and the detention unit. What is lacking, however, is any genuine readiness of the institutions and society in this country to take responsibility for the crimes committed during the Milošević regime. This, unfortunately, is further away at present than it used to be. Instead, what we have is a judge whose life is being threatened, a witness under police protection paying a high price for giving testimony, and police who question a witness just before his appearance in court. And all this to protect a Commander Boca, and others who profited from the war, senior officers and those guilty of wrongdoing in Srebrenica, Podujevo and many other places. Legislation on witness protection can lay down the best possible measures but who will encourage people to tell the truth in court if we all know that “the nation” would be best pleased with a law prohibiting the prosecution of any Serbs for war crimes.